Two Days in Provence: Tracing Lavender from Plant to Essential Oil

This blog was written by Lisa Bronner and originally appeared in her Going Green blog on September 25th 2025.

The heat bears down forcefully against my skin. The searing blue of a nearly cloudless sky presses in from overhead. The rocky limestone soil crunches beneath my feet as rows of purple haze rise and fall over the hills, contouring to the landscape. It is from this saturation of the senses that the most elegant of scents emerges: lavender essential oil.

Day 1, morning: How lavender grows

Here in the hills of southern Provence, France, I am absorbing a two-day crash course led by Philippe Soguel and his team from Distillerie Bleu Provence on all things lavender. Distillerie Bleu, a family business producing organic and fair trade essential oils, supplies Dr. Bronner’s with its lavender essential oils.

I am accompanied in this jaunt through the lavender fields by my husband Michael Milam, Dr. Bronner’s chief operating officer, and Dr. Bronner’s Special Ops team that facilitates the relationships between my family’s company, Dr. Bronner’s, and our ingredient suppliers around the world. My 16-year-old daughter has joined the fun, as well.

For an introduction to lavender, we are now standing with four or five farmers in a circle on the farm of Jacques Laget, a farmer and innovator in the cultivation of lavender. As several farmers share their background and farming stories, I am picking up more and more tidbits about this most revered of plants:

- Fine lavender and the lavender hybrid lavandin account for over half of acreage used for essential oils in Provence.

- The fields of the family farmers are scattered. While one farmer might grow 40 hectares (1 hectare = about 2.5 acres), they are rarely all adjacent. This long-inhabited land has boasted farms for millennia and when a couple hectares here or there becomes available for purchase, the farmers don’t hesitate.

- Lavender stems are square, as are most of the aromatic plants in the Lamiaceae family, which includes mint, oregano, sage, thyme, and most culinary herbs. Though I have grown all of these plants back home, I had never noticed that before.

- The plant named lavender came first. The color was named after the plant. The same is true with orange.

- The association between “lavender” and clean is more than sensory. The word itself comes from the Latin word “lavare,” meaning “to wash.”

The long history of cultivating lavender

Lavender has long permeated the human story. Egyptians used lavender in their mummification processes at least 2500 years ago. Native to the Mediterranean landscape, lavender soaks up the hot, dry climate, with many areas claiming preeminence for their region’s Lavandula—France, Spain, Italy, Bulgaria…

There are numerous varietals of lavender in the world, each with their own personality, profile, and purpose. But essential oils derive primarily from three. Lavandula angustifolia, whose coveted sweet scent finds its way into all manner of perfume and fragrance, grows at the higher altitudes between 1500 and 4500 feet. Down in the lower ranges of 900-1800 feet, you’ll find Lavandula latifolia, whose heavy concentration of camphor (upwards of 30%) relegates it to medicinal and therapeutic uses. In between these varieties on the hillsides grows a bee-produced hybrid of the two, Lavandula X intermedia, commonly called lavandin, which yields two to three times as much oil per hectare and blends the sweetness of angustifolia with the zest of latifolia.

When it comes to essential oils, the most prized lavender plant is Lavandula angustifolia, also called true lavender, fine lavender, mountain lavender, or, ironically, English lavender, so named for the market that made it so wildly popular. Of the 8,000 hectares of non-hybrid lavender under cultivation in France, 97% of that is angustifolia, while only 3% is latifolia. But most dominant of the Lavandula production is the oil-heavy lavandin, with 24,000 hectares under cultivation in France.

The field before me is lavandin, recognizable by the two side branches off of the central flower spike. Fine lavender only has the one straight spike, and this field is too high in elevation for latifolia.

The compounds in lavender essential oil

As I stand in the lavender fields, absorbing all this info, it is early in the lavender season. Late June. Still a month away from harvest, which happens when the flowers are just past their peak and hold the most oil. However, it’s not actually the flowers the farmers are watching. It’s the calyx, the small sac below the flower—or corolla—from which the flower emerges. It is the calyx which holds the precious oil.

Lavender plants produce oil to protect themselves from transpiration, or evaporative water loss. Therefore, the hotter it is, the more the plant produces oil as a defense mechanism. This is why harvesting happens during the hottest time of day in the hottest month of the year: August.

Essential oils are a complex blend of various compounds, which is why synthetic versions rarely come close to the multifaceted layers of real essentials. In lavender, the primary scent we identify comes from the two dominant naturally occurring compounds, linalool and linalyl acetate, which together comprise around half of the essential oil in L. angustifolia. In lavandin, camphor makes up another 10% or so and gives the oil that distinctive spicy note.

When people say lavender is “calming”, they are referring to angustifolia—English lavender, true lavender, mountain lavender. It has little camphor, focusing instead on the sweet linalool and linalyl acetate. Lavandin, on the other hand, true to its mid-elevation roots, is like the rambunctious middle child. A little bit sweet, a little bit punchy.

I’ve always been struck by that certain spicy note in Dr. Bronner’s Lavender Castile Magic Soap, a certain energy underlying the fresh and clean scent. My grandfather added the Lavender Castile to his product lineup in 1978, following Peppermint and Almond. It was the first scent he sold in bar soap form alongside the liquid. The lavender he composed is not the simple floral that synthetic versions of lavender have taught us to expect. In these fields of lavender, I found out why. The scent in the Lavender Magic Soap relies on a blend of two lavenders: the sweetness of Lavandula angustifolia paired with lavandin and its punchy hint of camphor.

At the moment, there is a gentle haze of lavender striping the hillsides. That haze will intensify to a deeper purple at harvest, and I am sorry that I won’t be here to see it.

Pursuing Regenerative Organic Certification in the lavender fields

All of the farmers around me are pursuing the new gold standard in product certification: Regenerative Organic Certified® (ROC™). The first pillar of the ROC standard is rebuilding soil health, with the other two pillars being fair trade and animal welfare. Here in Provence, land has been overfarmed for so many years, that there is next to no organic (living) matter in the rocky limestone soil. Farmers are tackling this deficit with two primary strategies: increasing soil fertility by growing and plowing under cover crops during the fields’ rest years and preventing nutrient and water loss by covering the soil in between the lavender rows with mulch and cover crops.

These farmers have measured approximately .8% organic matter in their soil, and it will take an input of 80 metric tons of plants plowed into the soil per hectare to restore it to a healthy baseline. This is a huge input. One farmer has been planting and sowing into his fields, in between the rows of lavenders, 3 rounds of alfalfa per year, and has been able in four years to raise the percentage of organic matter by 1%. This is considered excellent progress. It’s a long road ahead for these farmers.

Day 1, afternoon: Propagating & harvesting lavender

After an al fresco charcuterie lunch beside lavender fields beneath the shade of a towering chestnut tree (yes, it was as idyllic as it sounds), we are following Distillerie Bleu Provence’s agronomists Claire Leydet and Louise Bayart in our rented Corolla. (The rental agency was sorry they couldn’t fulfill Michael’s request for a French car. No Citroen? No Renault?). Suddenly, they pull over ahead of us, and Louise jumps out, grabs a wild flower from beside the road, and sprints to my window, which I roll down as she nears.

“This is clary sage!” She exclaimed earnestly, handing it to me before jumping back in her car to continue on. I hadn’t heard of clary sage, but a deep earthy and sweet scent quickly filled the car. A moment later Claire turns off the perfectly paved road on to what looks like little more than a rocky path between a vineyard and a hedgerow. Several hundred yards in, she stops and we pull up behind her.

I couldn’t tell why we were here. Before us is a field of rocks. A hot wind blows in our faces. A medieval town hunkers on the horizon, circular and dense. A vineyard grows to our right. Soon the farmer Bastien Long arrived to show us that we were looking at his lavandin field. Sure enough, the tufted lines sprouting out of the rocky expanse that I had overlooked as weeds are indeed lavandin, resilient enough to root and thrive in the inhospitable ground, proud of their hardiness and reluctance to be coddled.

“You anticipate these will actually grow here?”

“Oh, yes.”

Propagating lavender plants

Next we followed Bastien down the road to his lavandin nursery.

When it comes to propagation, there are two ways to reproduce fine lavender, but only one way to reproduce lavandin. Lavender that is grown from seed is called population lavender. Growing from seed results in a range of color and fragrance even within the same species. The plants may also be hardier, and more resistant to disease or insect infestation. Seed propagation adds a nuance and complexity to the resulting oil.

Only population lavender is eligible to receive the coveted AOP designation, or Appellation d’Origine Protégée (Protected Designation of Origin), verifying its origin and distillation within certain AOP designated regions, that it is grown from seed, and that it is truly representative of the species. This designation is meant to protect the reputation of the essential oil and ward off adulteration.

The second way to reproduce lavender is through cuttings, and this is called clonal lavender. The genetic identity of clonal plants are identical, resulting in identical color, profile, and fragrance. By using cuttings from an adult plant with specific desired characteristics, the farmer is assured that the resulting plants will have that certain trait, whether it is color of flowers, time of flowering, plant size, essential oil profile, oil yield, or specific pest resistance. Clonal plants mature much faster than population lavender, reaching first harvest around 18 months after planting, as opposed to 3-4 years.

Since lavandin is the sterile product of bees that have cross-pollinated angustifolia and latifolia, it cannot reproduce via seed. It can only reproduce via cuttings. Bastien prepares his fields of lavandin by taking 8-inch cuttings from adult lavandin plants and rooting them in dense rows in his home garden. It will take 30,000 cuttings to fill one hectare.

In additino to a sooner harvest, the advantage to lavandin is that despite the extra effort needed to get a field started, lavandin produces two to three times more oil per hectare than fine lavender plants. Also, with its lower elevation, it is hardier and more accessible.

Harvesting lavender flowers

A little over a month after my visit, the plants will be ready for their annual harvest. Lavender is a perennial plant, as opposed to an annual, which means it keeps growing year after year. On average, one field of lavender grows for 7-10 years, until the plants get too big for the harvester. There is value to this cycle, though, because letting the fields lie fallow, or rest, for one or two years in between the years of growth allows them to regain their nutrient density and moisture. Or, farmers might boost the organic matter during this time by planting cover crops like legumes, alfalfa, or clover which then are plowed back into the soil.

It is important in harvesting the lavender to remove only the soft, recent growth, and not to damage the woody part of the plant. Lavender plants that are sheared too closely might not recover or bloom well the following year.

Innovations in harvesting with L’Espieur harvester

One theme I admired greatly amongst the farmers was their resourcefulness and innovation. These farmers are not connected to well-funded global enterprises. For many of them, growing lavender is a supplemental enterprise, or they have another enterprise that pays the bills. All that to say, there are neither resources nor justification for purchasing new, single-purpose farm machinery. Instead, they have repurposed machinery bought from larger farms and reconfigured them to their needs.

The Espieur harvester is a story in innovation resulting in conservation of fuel and time, while also improving field health and oil yield. Farmer Jacques Laget purchased an old cereal crop harvester and then removed the center blades so that the lavender plants can pass beneath without harm. He further modified the blades so that they simultaneously comb the lavender stems while cutting them. Combing the stems removes and captures only the flowers while the cut stems are crushed beneath the harvester and left between the lavender rows to become mulch and help maintain soil moisture.

This ability of the Espieur to capture only the flowers results in a number of savings. Only the flowers on the lavender plant yield oil. The stems provide no value in the distillation. By harvesting only the flowers, with minimal stems, Jacques is able to maximize his truck space in transporting his crop to the distillery, 30 minutes away, resulting in fewer trips, thereby using less fuel and less time.

Without stems uselessly taking up space in the steam pots (more on those in a moment), each batch produces three times more oil than batches that include stems. This results in faster processing and reduction in the energy and water that goes into the steam production. The production of steam is the most expensive part of the distillation process, so eliminating one or two batches of steam adds up to significant savings.

Care is also taken in the harvesting to protect the bees that are invaluable to pollination. With the harvest machinery that operate at a low speed, the slow oncoming rumble is enough warning to urge the bees to relocate. Harvesters that move faster, around 6 km/hour, are equipped with a rod that extends in front of the machine to brush the plants, dislodging any visiting bees.

Day 2: Distilling lavender essential oil

The next day found us headed back to Distillerie Bleu Provence which I had only seen in passing the day before.

Distillerie Bleu Provence is nestled in the village of Nyons (I learned the second “n” is dropped in pronunciation), along the Eygues River in the southern part of Provence. Nyons is a small market town with a delightful Sunday morning market where I ogled the olives, breads, and cheeses, while my daughter gloried in the clothing boutiques and jewelry.

Near the distillery a gorgeous 14th century Romanesque Bridge still carries traffic over the Eygues, vaulting the river in a single elegant 43 meter arch, soaring 18 meters from the river below. I was riveted by that bridge. In my mind’s eye, I saw the hands crafting that bridge without modern machinery—measuring, hewing, fitting stones in place. Oh the arrogance of modernity to think that we have the monopoly on engineering and audacity. This bridge stands in testament to the daring and vision of the past.

Distillerie Bleu distills many types of essential oils

As I walked towards Distillerie Bleu, an undeniable wave of nostalgia for my mom’s homemade spaghetti sauce engulfed me. It was her signature dish during cool weather, made in a pot reserved exclusively for that purpose, tantalizing and tormenting us all day until at long last dinner time arrived. Her spaghetti was the embodiment of all that was comforting and fulfilling from my childhood. What brought that to mind here, now, on this heavily hot day in this far away place?

“We’re distilling oregano today,” Phillipe explained, as we walked up. That would do it.

The aroma of oregano enveloped the town for blocks. I would imagine the neighbors can tell the time of year by the aromas wafting through their streets from the distillery. That sounds like a delightful way to track time!

The process of steam distilling lavender essential oil

The practice of steam distillation is over 5,000 years old, but advancements in energy efficiency and water conservation have refined the best of what’s been. This is a perfect example of antiquity and modernity working in tandem.

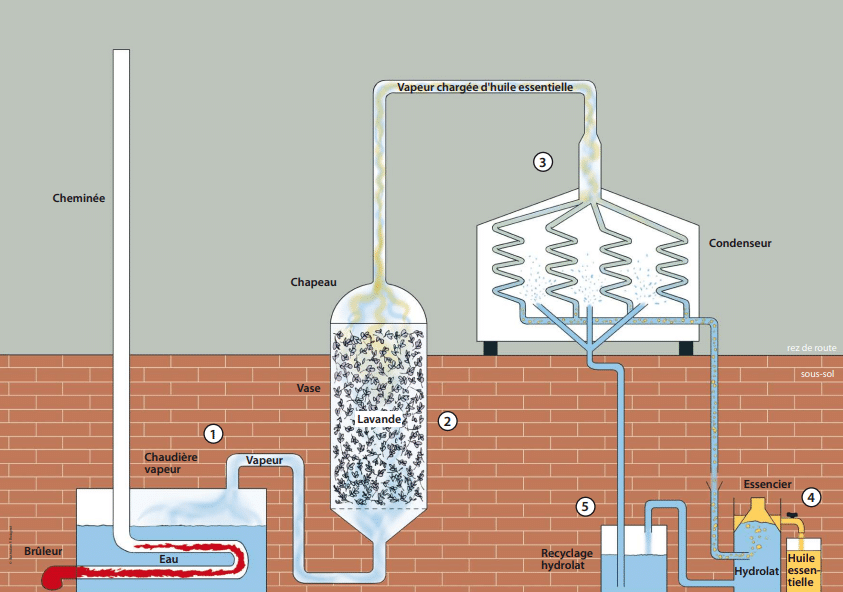

Before me is where farmers bring their truckloads of lavender, oregano, thyme, sage and more to distill into essential oils using steam distillation. Farmers drive straight under the porte cochere beside the ranks of condensing coils and steam pots. Then, using pitchforks, they pitch the plant matter from the truck beds into the steam pots. The 6 cubic meter stainless steel steam pots (over 1500 gallons) are built into the floor, with their bottom half disappearing into the cellar beneath. Distilling technicians positioned beside the steam pots pack down the plants, aided by a giant concrete tamper.

With a pressure-withstanding lid affixed in place, a technician attaches a steam hose to the bottom of the steam pot and begins pumping 1 metric ton of steam per hour through the vessel. The steam heats the plants enough to release their captive liquor and carry it upwards. Controlling the heat of the steam is pivotal. Too hot and the plant cooks resulting in bitter oil. Too cool and much of the precious compound gets left behind and the process takes too long, resulting in more fuel usage and poorer quality oil. The goal is to keep the steam at a constant 100°C.

The steam rises through the plant matter, heating and vaporizing the essential oil, and carrying it on its journey upwards. Another hose affixed to an outlet in the lid leads the water/oil vapor into the condenser coils marshalled in rows beside the steam pots. These coils receive the vapor and convert the gaseous mixture into usable liquid.

The vapor winds its way down through the coils while the outside of the coils are sprayed with water. The water spray utilizes the power of evaporative cooling, which means that as the water evaporates off of the outside of the coils, it takes with it the heat from the hot vapor within the coils. Eventually the evaporation brings the vapor temperature down to 25-35°C by which point it has condensed into liquid.

The now liquid oil-water mixture drains out the bottom of the coils into another vessel in the cellar below. Gravity acts on density to separate the oil and water. No fancy equipment is needed. No mechanization. The pull of the earth’s gravity against the weight of molecules – an ancient, irresistible, and fundamental force – causes the water to sink beneath the oil.

As the oil rises to the top of the vessel, it flows out through a sort of inverted wide-mouth funnel with a spout. It then passes through a filter to catch any wayward debris. The water is collected for further use. And that’s it. The oil is finished, ready to be bottled, whether it’s in 1 oz. vials for individual sale or 1,000 liter totes for shipping to Dr. Bronner’s headquarters in Vista, CA. Minimal processing. No adulteration.

The yield from each batch of plants that runs through the steam pots varies by type. True lavender that is harvested without the Espieur yields about 10 kg of oil, while lavendin gives 20-30 kg of oil. With the Espieur harvest, the oil yield is two or three times that amount.

There is no waste in steam distillation of essential oils

There are two leftovers from this process: the plant matter left in the steam pots and the water separated from the oil. Neither of these go to waste. The plant matter is sent back to the farms to become compost, which will be spread on the fields to nourish ongoing lavender crops.

The separated water is a “hydrosol,” meaning “water-solution,” and carries compounds of the plant essence, making it faintly scented. If the batch of herbs was organic, the resulting hydrosol has value to manufacturers of organic body care products and is sold off as an ingredient. If the batch was conventional (non-organic), the hydrosol has no resale value but is collected and used for the evaporative cooling spray in a subsequent batch of oil.

Steam distillation harnesses natural forces

So much of this process is working in sync with natural processes. The rising nature of steam at just the right temperature gently draws the oils from the plants. A spray of water on the condensing coils allows evaporative cooling to liquify the oil/water vapor. Gravity interacts with density to separate the oil from the water. It’s an understanding, a dance of sorts, between nature’s principles and knowledgeable technicians.

The circularity of this process that puts every output to use is elegant and efficient. The beautiful simplicity and chemistry reminds me greatly of saponification, the reaction that makes soap and is at the core of my family’s business today. Both saponification and distillation are ancient processes, improved but not fundamentally changed by recent innovation.

Back home with my lavender soap

Back at Dr. Bronner’s headquarters in Vista, CA, I see the lavender totes arrive as an ingredient for a variety of products. Lavender is the second most popular scent in our product line, after Peppermint, appearing not only in the bar and liquid Magic Soap, but also in the Organic Sugar Soaps, Organic Shaving Soaps, Organic Hair Crème, Organic Hand & Body Lotion, and Organic Hand Sanitizer. Now I can look into each bottle and picture their origin.

I brought a few vials of L. angustifolia home with me straight from Distillerie Bleu’s gift shop, and as I incorporate it into my GIY (Green-It-Yourself) recipes, I see the journey of each droplet – the plant that grew it, the farmers that nurtured it, the technicians that extracted it, the hands that bottled it. The essence of a legacy captured in each liquid form. As rich as the scent was already, it is now infinitely richer for me.

Enjoy this gorgeous video from Distillerie Bleu showing the journey of lavender, from field to distillery.

Leave a comment